Brimlow/Brimalow/Broomelaw/Bromilow

Making the leap across the pond requires an understanding and acceptance of pronunciation and spelling. While the people who recorded the information were required to be able to read and write, they were not required to know how to spell. Spelling has been optional since the beginning of written records. Our names were really only hammered into some semblance of a final form when the federal government got involved. Many people believe that occurred with the advent of standardized birth records in the early 1900s and then solidified when Social Security came along. Once the government had your name spelled a certain way, then that’s the way it would always be unless you legally changed it.

But the spelling issue came much earlier for some people. Men who served in the military kept the name they enlisted under for government records – Henry and Robert Pickel both served in the Civil War under the name Pickel but after the war reverted to the original form of the name Bickel. They were not the first with the problem. The family story is that their great grandfather Tobias Bickel had served in the Revolutionary War but when he enlisted, his accent made the “B” sound like a “P” to company clerk, so he became Tobias Pickel on the records. Most of the Bickel/Pickel men used both spellings throughout their lives and I have found marriage records for one man under both names. I have seen brothers who each used a different spelling. John Pickel used Pickel throughout his life, while his brothers Henry and Robert started as Pickel but switched to Bickel after the war except when applying for their pensions and then they used Pickel again.

While it appears our ancestor’s name solidified to Brimlow (with just the usual spelling issues Bremlow/Bramlow/Brenlow/Brimbow) by about 1840 in New York, prior to that, it’s totally up for grabs and you have to be flexible in the investigation. According to the all-knowing website, The Internet Surname Database, the name Brimlow/Brimelow “…derive from the place called Bromlow in Shropshire: The place name has generated a number of variant surnames, as the bearers of the name moved to other areas and dialectal differences produced varying phonetic spellings, among them Bromilow, Brumloe, Brimelow and Bromblow. The original place name is recorded as “Bromlawe” in the 1255 Shropshire Hundred Rolls, and means “the broom-covered hill”, derived from the Olde English pre 7th Century “brom”, broom, with “hlaw, hlaew”, low hill, mound. …The first recorded spelling of the family name is shown to be that of Richard Bromlowe, which was dated May 28th 1534, marriage to Helenora Marsh, at Church Pulverbath, Shropshire…”

The reason to bring up the name discussion here is as a forewarning of what is to come. You can expect to see a wide variety of records when we make that leap across the pond and the discussion of “what should his name really be” is always fun to have. Do you go with the name he used as an adult, or list him with the name that appears in the baptism register? An evolving name is the bane of every genealogist because the names may change several times within a generation. You also can’t trust his signature. As stated, names evolve.

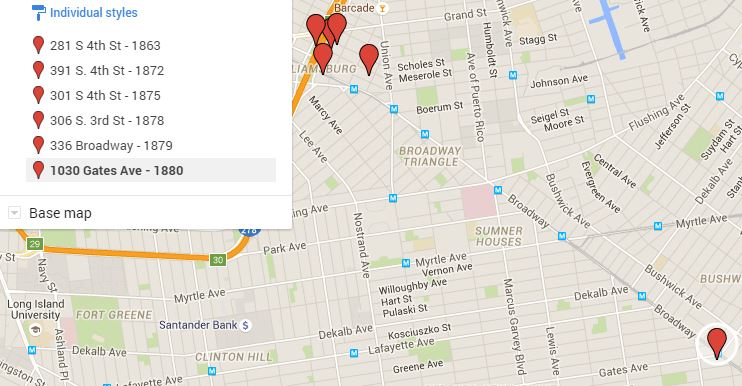

For all of the above reasons, I’m going to break the posts on William Bromilow/Brimalow/Broomelaw/Brimlow into several pieces. I’ll begin with William and Ann Brimlow from the arrival of the family in New York through death, because you can’t make the leap across the pond without all the little bits and pieces you know about the family to begin with. Knowing who the children are is key to locating the family in England. The next post will be about locating them in England and pinning down the family. Somewhere along the way we have to talk about the towns and villages and the occupations. It’ll be a complete disaster as far as the order of things, but in the end, you’ll know everything I know and hopefully understand why I came to the conclusions I did. And if you think I’m wrong, send me your chart with sources, and I’ll give it a serious look. Lord knows, I’ve barked up a few wrong trees before.